REVIEWS

DECLARATION

Cathedralism is a movement of the individual—focusing on the interaction between the user (the viewer) and the medium (film).

To write about a movie and focus on its actors, color grading, cinematography, dialogue or any other technique or aspect of the work is an important part of digesting the just-watched work, but then on its watch for others, when they see it, that written review becomes invalid. From an objective perspective the audience will see all of the written aspects that another would spend time noting in their review—and if the audience doesn’t catch what’d been written, then a rewatch would cure the ailment, and, again, the review would be voided. But what is important, and one of the sole reasons why people watch movies, is their relation to the work. This experience varies for each user. This—this engraving of feeling and thoughts and memories and observations—holds importance because it is the intimate, real and beautiful connection between a person and the thing which they’ve spent their always-thinning time with. It is only the individual experience that is important.

As many consume to share with friends the highlights or observations of a movie on car trips or lunches or in passing and to only, ultimately, reiterate the already known—just to have something to say and agree with under the false blanket of connection—the commonality they find between each other is vacant, as nothing about either person is learned; nothing changes. Even observing a movie through a critical or philosophical perspective can only do so much; only if the consumer meditates, reacts to, and incorporates these ideas into their lives then the theories become important; but without the connection, whatever facts that are brought up are “as sounding brass, or a tinkling cymbal”—nothing. Again, if the theories matter, it is only because they have been integrated into the user’s intimate viewing experience—an experience that deserves to be recorded as the process of living surpasses the product.

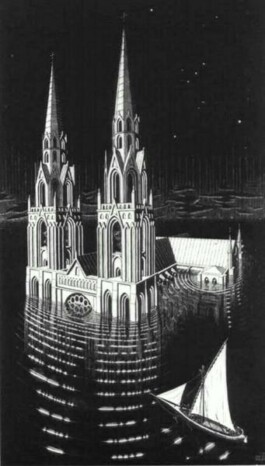

In Raymond Carver’s “Cathedral,” a man and wife host a blind man at their house where conversation is sparse—or conversation without meaning dominates—and the hosting man turns on the TV. The blind man obviously cannot see the program: a show touring cathedrals, so the man (the host) describes what is being shown on TV to the other. Unable to really understand what’s going on, the blind man has the other draw a cathedral on paper with the blind man’s hands over his. By the end of their activity the drawing man is changed. The activity transforms him. He encounters the irrational that connects him to the distanced-other that had guided him through his interaction; this encounter is then assumed to shape the man’s relationship with his wife, who he’s also emotionally distanced from. And it is the TV program which triggered this; but it’s important to note that it isn’t the cathedral program that changed the man; it's the person he watched it with, the commentary during it, the involvement inspired afterwards, etc.

Carver’s story shows us, consumers, how we should handle media. It is less about the program, the show, the film, etc., and more about the happening. About the change in which the audience undergoes through consumption. About the setting it was consumed in, the people it was consumed with, etc. In the story the TV program’s only value was to prompt and situate an experience for the man.

An example: it matters less that a movie shocked you and more in how it shocked you. What matters is the theater or basement where you watched it. What matters is the people that shared the couch with you and the conversations before, during, and after the film; the scents of the street through the open window near the TV, the taste of the cheap snacks, the thoughts about your romantic partner who you sit by but haven’t spoken to honestly, truly, the entire day because of an argument but now share a beanbag with and watch a movie together and why you’re able to do that but not communicate. Whatever the reasons may be, those are what are important, more so than a catalogue of the film’s score, shot composition, etc. What a viewer writes about concerning the film in regards to its qualities holds no value as those qualities in the film will exist before and after the review is written, forever unchanged—but the viewer themselves watch the film with a variety of differing variables, shifting emotions, distracted thoughts, emotional responses. When a movie prompts a viewer to hug someone, to text their mother, to start exercising again . . . those are what that actually matter. Because those are real. Those are important. Because they are you.

The attachment of oneself to the media and cataloging this relation in a review also creates moments of introspection, similar to journaling. If a film touches the viewer because of the calmness of its main character, they, through their writing, can express the significance of that portrayal through memories or current circumstances. Rather than discussing how well the actor did, the now-writing viewer can describe what it was like for them growing up in a stressful household where there was never enough yet they had to be calm in order to avoid excessive punishment; the actor triggers these emotions within the viewer, placing them in observation with their Self. Instead of the movie being solely a space of time spent in a dark room, the intimate, highly individual review turns it into a relic of memory, growth, change.

The term Cathedralism comes both from Carver's story and the cathedral's symbolism. What is religion without relationship? The Bible would only be another book on a shelf if not for attachment. A cathedral would only be admired for its workmanship and not its spiritual reverence through observation or found within; a reverence that only comes from experience with. Experience and recognition of is the only thing that ascribes any sort of life-meaning, and without it, an existential dichotomy is raised: “Either we live by accident and die by accident, or we live by plan and die by plan.” If we deny the threading of our experiences we deny structure, purpose. But by removing a film from its objective form and internalizing it, describing its surroundings and the significance of that, the stream-of-consciousness experienced throughout it—then meaning is formed.

Now these ramblings of experience, memory, association are nothing new—everyone holds their own subjective experiences which shape who they are. But why are film reviews—which consistently vary from person to person, showcasing film’s inherent subjectivity, yet which differences or objections are only discussed in their reviews through facets of the film and not their individual relationship to—still primarily written as summaries of facts already known or soon to be realized? What actually matters is the association of the film in all of its atmosphere and setting with the consumer. Because that is human. That is important. Not the film trivia, but the consumer themselves—no longer displaced; now at the axis.

CATHEDRALISM'S VOW OF CHASTITY

1. The film review is personal—even reaching narrative.

2. The film review has minimal mentions of the film.

3. No mention of any technical aspect within the film.

4. The subject of the review is the writer, the viewer, the “I.” All reviews must be written from the first-person perspective. This includes an inferred first-person perspective: the other characters are observed by the writer.

5. Each review must be told through a personal memory—authentic to how it’s remembered—, regardless of historical accuracy.

Realized,

George Dibble, Ethan Taylor

DECLARATION

To write about a movie and focus on its actors, color grading, cinematography, dialogue or any other technique or aspect of the work is an important part of digesting the just-watched work, but then on its watch for others, when they see it, that written review becomes invalid. From an objective perspective the audience will see all of the written aspects that another would spend time noting in their review—and if the audience doesn’t catch what’d been written, then a rewatch would cure the ailment, and, again, the review would be voided. But what is important, and one of the sole reasons why people watch movies, is their relation to the work. This experience varies for each user. This—this engraving of feeling and thoughts and memories and observations—holds importance because it is the intimate, real and beautiful connection between a person and the thing which they’ve spent their always-thinning time with. It is only the individual experience that is important.

As many consume to share with friends the highlights or observations of a movie on car trips or lunches or in passing and to only, ultimately, reiterate the already known—just to have something to say and agree with under the false blanket of connection—the commonality they find between each other is vacant, as nothing about either person is learned; nothing changes. Even observing a movie through a critical or philosophical perspective can only do so much; only if the consumer meditates, reacts to, and incorporates these ideas into their lives then the theories become important; but without the connection, whatever facts that are brought up are “as sounding brass, or a tinkling cymbal”—nothing. Again, if the theories matter, it is only because they have been integrated into the user’s intimate viewing experience—an experience that deserves to be recorded as the process of living surpasses the product.

In Raymond Carver’s “Cathedral,” a man and wife host a blind man at their house where conversation is sparse—or conversation without meaning dominates—and the hosting man turns on the TV. The blind man obviously cannot see the program: a show touring cathedrals, so the man (the host) describes what is being shown on TV to the other. Unable to really understand what’s going on, the blind man has the other draw a cathedral on paper with the blind man’s hands over his. By the end of their activity the drawing man is changed. The activity transforms him. He encounters the irrational that connects him to the distanced-other that had guided him through his interaction; this encounter is then assumed to shape the man’s relationship with his wife, who he’s also emotionally distanced from. And it is the TV program which triggered this; but it’s important to note that it isn’t the cathedral program that changed the man; it's the person he watched it with, the commentary during it, the involvement inspired afterwards, etc.

Carver’s story shows us, consumers, how we should handle media. It is less about the program, the show, the film, etc., and more about the happening. About the change in which the audience undergoes through consumption. About the setting it was consumed in, the people it was consumed with, etc. In the story the TV program’s only value was to prompt and situate an experience for the man.

An example: it matters less that a movie shocked you and more in how it shocked you. What matters is the theater or basement where you watched it. What matters is the people that shared the couch with you and the conversations before, during, and after the film; the scents of the street through the open window near the TV, the taste of the cheap snacks, the thoughts about your romantic partner who you sit by but haven’t spoken to honestly, truly, the entire day because of an argument but now share a beanbag with and watch a movie together and why you’re able to do that but not communicate. Whatever the reasons may be, those are what are important, more so than a catalogue of the film’s score, shot composition, etc. What a viewer writes about concerning the film in regards to its qualities holds no value as those qualities in the film will exist before and after the review is written, forever unchanged—but the viewer themselves watch the film with a variety of differing variables, shifting emotions, distracted thoughts, emotional responses. When a movie prompts a viewer to hug someone, to text their mother, to start exercising again . . . those are what that actually matter. Because those are real. Those are important. Because they are you.

The attachment of oneself to the media and cataloging this relation in a review also creates moments of introspection, similar to journaling. If a film touches the viewer because of the calmness of its main character, they, through their writing, can express the significance of that portrayal through memories or current circumstances. Rather than discussing how well the actor did, the now-writing viewer can describe what it was like for them growing up in a stressful household where there was never enough yet they had to be calm in order to avoid excessive punishment; the actor triggers these emotions within the viewer, placing them in observation with their Self. Instead of the movie being solely a space of time spent in a dark room, the intimate, highly individual review turns it into a relic of memory, growth, change.

The term Cathedralism comes both from Carver's story and the cathedral's symbolism. What is religion without relationship? The Bible would only be another book on a shelf if not for attachment. A cathedral would only be admired for its workmanship and not its spiritual reverence through observation or found within; a reverence that only comes from experience with. Experience and recognition of is the only thing that ascribes any sort of life-meaning, and without it, an existential dichotomy is raised: “Either we live by accident and die by accident, or we live by plan and die by plan.” If we deny the threading of our experiences we deny structure, purpose. But by removing a film from its objective form and internalizing it, describing its surroundings and the significance of that, the stream-of-consciousness experienced throughout it—then meaning is formed.

Now these ramblings of experience, memory, association are nothing new—everyone holds their own subjective experiences which shape who they are. But why are film reviews—which consistently vary from person to person, showcasing film’s inherent subjectivity, yet which differences or objections are only discussed in their reviews through facets of the film and not their individual relationship to—still primarily written as summaries of facts already known or soon to be realized? What actually matters is the association of the film in all of its atmosphere and setting with the consumer. Because that is human. That is important. Not the film trivia, but the consumer themselves—no longer displaced; now at the axis.

CATHEDRALISM'S VOW OF CHASTITY

1. The film review is personal—even reaching narrative.

2. The film review has minimal mentions of the film.

3. No mention of any technical aspect within the film.

4. The subject of the review is the writer, the viewer, the “I.” All reviews must be written from the first-person perspective. This includes an inferred first-person perspective: the other characters are observed by the writer.

5. Each review must be told through a personal memory—authentic to how it’s remembered—, regardless of historical accuracy.

Realized,

George Dibble, Ethan Taylor